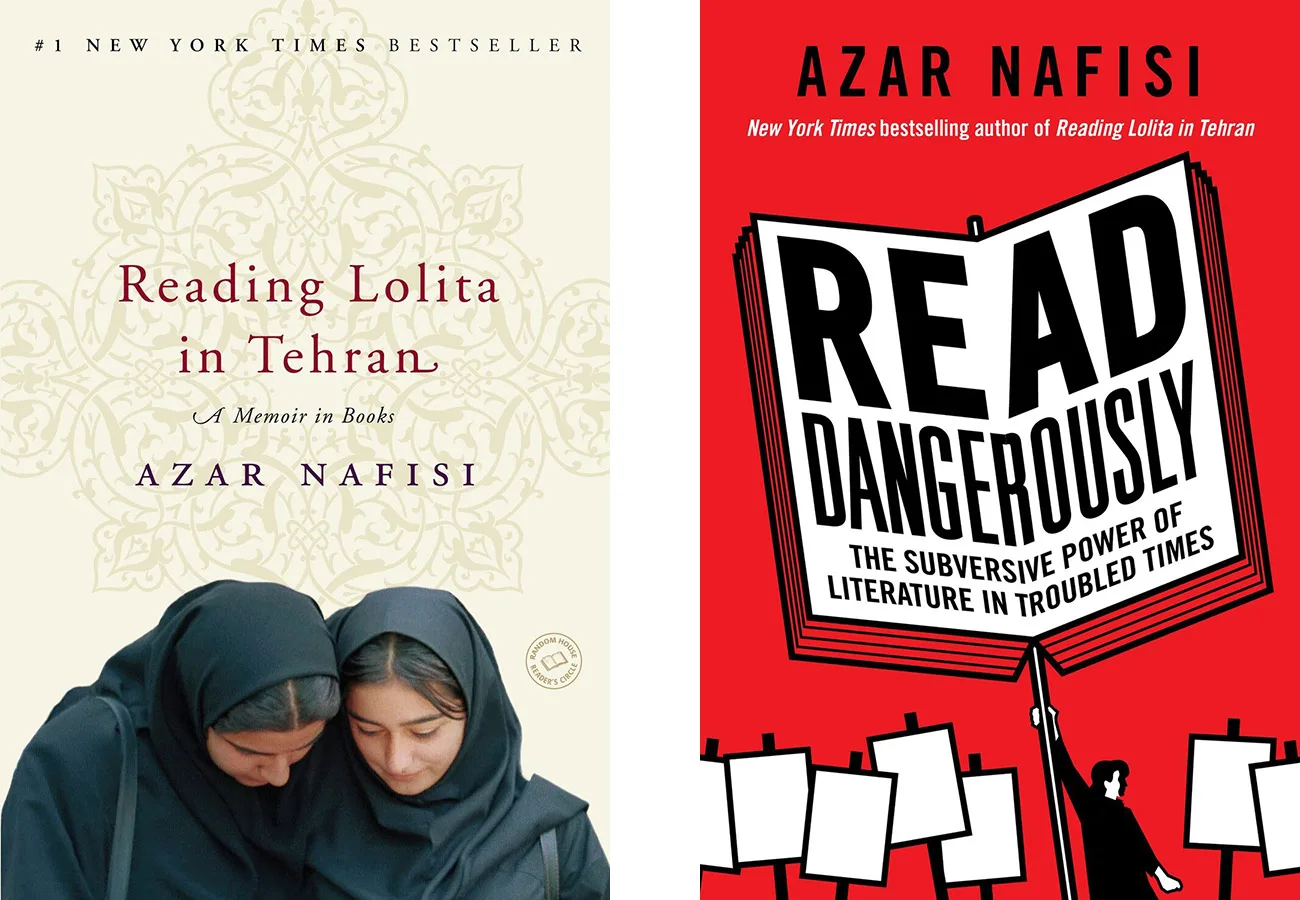

Gifted with a literary voice as compelling as it is compassionate, Azar Nafisi is widely celebrated for her profound narratives that bridge cultural divides. Her most acclaimed work, Reading Lolita in Tehran, not only captivates audiences with its riveting prose, but also serves as a testament to Nafisi’s belief in storytelling as a tool for empowerment – a belief that has resonated deeply on a global scale.

In exploring the enduring power of literature, Nafisi illuminates its ability to provoke empathy, challenge perceptions and inspire change. As an Iranian writer, she deftly intertwines personal experiences with universal themes, crafting tales that transcend borders and resonate across generations. Read on to find out what she has to say about the role of storytelling in fostering community, as well as the many ways imagination can shape our world.

Amex Essentials: What inspired you to become a writer?

Azar Nafisi: Before I was a writer, I was a reader. And before I was a reader, I was a listener. My father, when I was about three, would at night tell me a story. As I grew up, we expanded those storytelling sessions to me participating in the stories. He was very democratic in his storytelling. One night, we would be with mythical creatures created by our great epic poet Ferdowsī; the next, we would be in France with the Little Prince, the next day, in England with Alice, in Italy with Pinnocchio, or in the US with Charlotte’s web.

I learned very early on that I could stay in my little room and the whole world could come to me through stories. And then one game my father and I played when I was older was that we communicated through storytelling. Whenever he was angry with me, he wouldn’t show his anger. He would usually take my hand, go for a walk and say, “There was this man who loved his little daughter but she…” And so I learned from very early childhood to communicate through stories.

Later came my diaries. I was nine years old when I started my first one. All my life, through my family, we were only snobbish about books. Other people judged one another through power or money. We judged them through how many books they read, and how involved they were with storytelling. I can tell you that reading inspired writing, by the desire to want to communicate something that seems not communicable.

A lot of your writing – from your latest, Read Dangerously, all the way back to Reading Lolita in Tehran – is structured around canonical works of literature. What’s the importance of reading the classics in our day and age?

The truth of the matter is that imaginative knowledge is a way of looking at the world, relating and connecting to the world, and changing the world. It has been with us since we called ourselves human. As human beings, we need to know others. We keep talking about the other, but we don’t really appreciate that if you want to know the other, you have to come out of yourself.

These days, we condemn those works of art that are not about us currently, while these works of art talk about what is enduring. Through this curiosity about others, we connect to others, we connect to the world, we create empathy. And without empathy we’re all dead.

This is what is so dangerous today, this lack of empathy towards those who are not like us. Storytelling, for thousands of years, has been addressing not just the current issues, but the enduring issues. Why is it that we need human rights, why is it that we need literature that endures? Human beings need connection to the past. Life is fickle, every moment we die, and we need to preserve that which keeps dying. That is why we tell stories, because they are conclusive evidence that we have lived.

I want to remind people of this Greek tragedy play called Antigone. It is about making a choice between your loyalties to the individual, to the self, or loyalty to the state – and about how people, like Antigone, are prepared to give their life for their values. Now tell me this is not relevant to today, that we don’t need to think about individual choices, individual values. I’d tell you that you cannot appreciate either life or stories if you think that way.

Your books explore the themes of resistance and resilience. How can individuals today effectively resist oppressive forces that restrain personal liberties and denounce plural cultural identities?

You know, I learned a lot about this when I was living in the Islamic Republic of Iran. I was then dealing with what we’re dealing with now in America, with a totalitarian mindset. And a totalitarian mindset, its first targets are women, minorities and culture. They are so scared of them. People don’t realise, they see the power and violence, they don’t know that these things don’t come out of strength, but out of weakness. They are afraid of women, and want them to become invisible, to be covered when they are in public.

The matter of fighting this kind of mindset is an existential one, not a political one. A lot of times when I talk about resistance, people ask me why I’m so political. No, I say, I’m not being political, I don’t belong to a political party, I don’t have an ideology. I am fighting for my existence as a woman, as a teacher, as a writer, as a reader. As someone who believes in human rights, my rights are being taken away from me. My identity as a woman is being taken away from me. I feel mutilated.

In Iran, when we went out we had to change our identity, who we were. We had to go underground for what we were. And what did the Iranian people do? They decided to use what they were trying to take away from us. As they killed and jailed artists and poets and writers, Iranian people read more and more of their works. They made the words into weapons. They were even killed for not wearing the veil. They were harassed, killed, tortured. And what did they do? They came to the streets of Tehran and threw their mandatory veil into the fire and started singing and dancing. They turned the streets of Tehran into a place of war, but that war is that, on one side, there were bullets, and on the other side there were voices singing and dancing, celebrating life.

Now what do I think we should do in the United States? We should take this war not just as a political one, but as an existential one. It is about our individual lives, it is about who we are, and we need to protect who we are. That is why we need stories, why we need history. We need to read history to understand who we were and who we want to be, and not allow someone like Ayatollah Khomeini or Donald Trump to take away our identity, as human beings, as Americans, and as individuals.

As someone with such a deep-rooted connection to Iran, how has living in the US changed your perspective?

Before I came to America, I hadn’t been here in 18 years, so I had some illusions. Two things that were most important for me when I came, that were really my bread and water, were freedom of association and freedom of expression. They made me feel like a citizen when I could express myself no matter what I said, and so that brought about a lot of change.

I felt so free at the beginning. I constantly wanted to talk about things that I had been silent about. Both of these are now in danger in the United States. Loving a country, becoming a citizen of a country, doesn’t mean that you unconditionally love it. It means that you see the faults. When I realise that I’m criticising America, I realise that now I want to be an American, because I want to make a change. To be an American, for me, means accepting the other and accepting change.

Your book Things I’ve Been Silent About delves into your personal history. How did the process of writing a memoir impact your understanding of your own life experiences? Did you find that your memories were transformed as you put them down in writing?

Yes, they do change a great deal. Some people think that, in the act of writing, you know from the beginning what you want to write. That is completely wrong. You write because you want to investigate. They asked Margaret Atwood how she starts writing. She said, “I think voices from distant villages beckon to me,” that you find a knife in the middle of the living room and you ask yourself, “Hmm what’s that knife doing there? It needs to be investigated.” So for me, Things I’ve Been Silent About was definitely a journey I thought I knew, but I didn’t.

When my parents passed away, I felt that there was so much I needed to talk to them about, and I had missed that opportunity. One of the things that changed a great deal for me was my relationship with my mother. When I started writing, I started it with some resentment. I had a very difficult childhood, and I had so many problems with her. Then, as I started writing I realised her pain, because I had to write about her pain as well, not just mine, her loneliness, her suffering – I discovered them. By the end of the memoir, my tone changes, I feel more understanding of her, and I feel that my father was less the idealistic character I had thought him to be. I felt that by making my peace with my mother, I made my peace with myself.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Your book Read Dangerously is structured as a series of letters to your late father. Why did you opt for letters, as opposed to a more conventional structure? What does letter writing mean to you as an author?

Thank you for this question. Well, exactly because I was bored with the conventional way of writing essays. Once you get bored with something you write, definitely stop. It took me a long time, I kept thinking of different forms, and they didn’t come. A friend asked me, “Why don’t you write about someone in the third person? You keep talking about talking to others, exchanging with others, so why don’t you do what you say you want to do, which is exchange?” I thought yeah, she’s right, now who do I want to exchange things with? My father was the first person that came to my mind.

My father and I, as I mentioned, through stories, through letter writing, kept our relationship going forever. And I wanted to write something that was both personal and intimate, so that the reader could feel what I was writing, not just with their mind but with their heart. I also wanted to talk about ideas, but how could I merge the two? Through writing to my father. He went to America to continue his education for a year when I was six years old, and that is when our letter writing started. We wrote throughout the ages, until he was near death we wrote to one another. From the taste of ice cream and how good it is, to philosophical issues, political issues of the day, we wrote. I wanted to share that with the world.

What is your advice to readers who may be thinking about writing a book of their own, be it a novel or a work of nonfiction?

Writing is exciting and refreshing and difficult and torturous, you know? You suffer through a book, because you are talking about the things that most matter to you. If you cheat the reader by making up things that you don’t really feel, they realise it.

I’m very bad at giving advice, but for me, you need to have passion. For me, it’s a process like falling in love. You meet this person and somehow, you don’t know why, something clicks. You need to investigate what is clicking. And you go into it. Writing, like love, is both difficult and torturous. It’s also beautiful and life-giving and mischievous. You need to be mischievous. A good writer is always mischievous, and doesn’t take themselves too seriously.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.