Three years ago, nomadic French artist Hervé di Rosa accepted the challenge to create a show based on a highly original concept, but for once he wouldn’t have to travel far. Di Rosa – who has spent the last two decades country-hopping between four continents to learn about ancestral artisanal techniques – prepared for his latest exhibition at Marseille’s portside MUCEM (Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée) through an intuitive voyage that connected the past with the present.

Call it a joyride in time travel: for weeks, the artist roamed through the storage facilities of MUCEM’s immense revolving collection, which houses over 350,000 carefully organised pieces and artifacts from different eras and Mediterranean civilisations. As the days went by, he would stumble upon a rarely shown object hidden away in the stacks that resonated with the exuberant spirit of his work.

“It felt like walking through a giant amusement park – I tend to like things that have a rapport with carnivals, fairs or antique merry-go-rounds,” Di Rosa says with a grin. “But not only the grotesque. I also chose objects like oxen yokes, bowling pins, wooden decoy ducks or Sicilian marionettes. I’m a contemporary artist who revitalises folk art and old objects that people no longer use.”

[Images: © Pierre Schwartz / Victoire di Rosa]

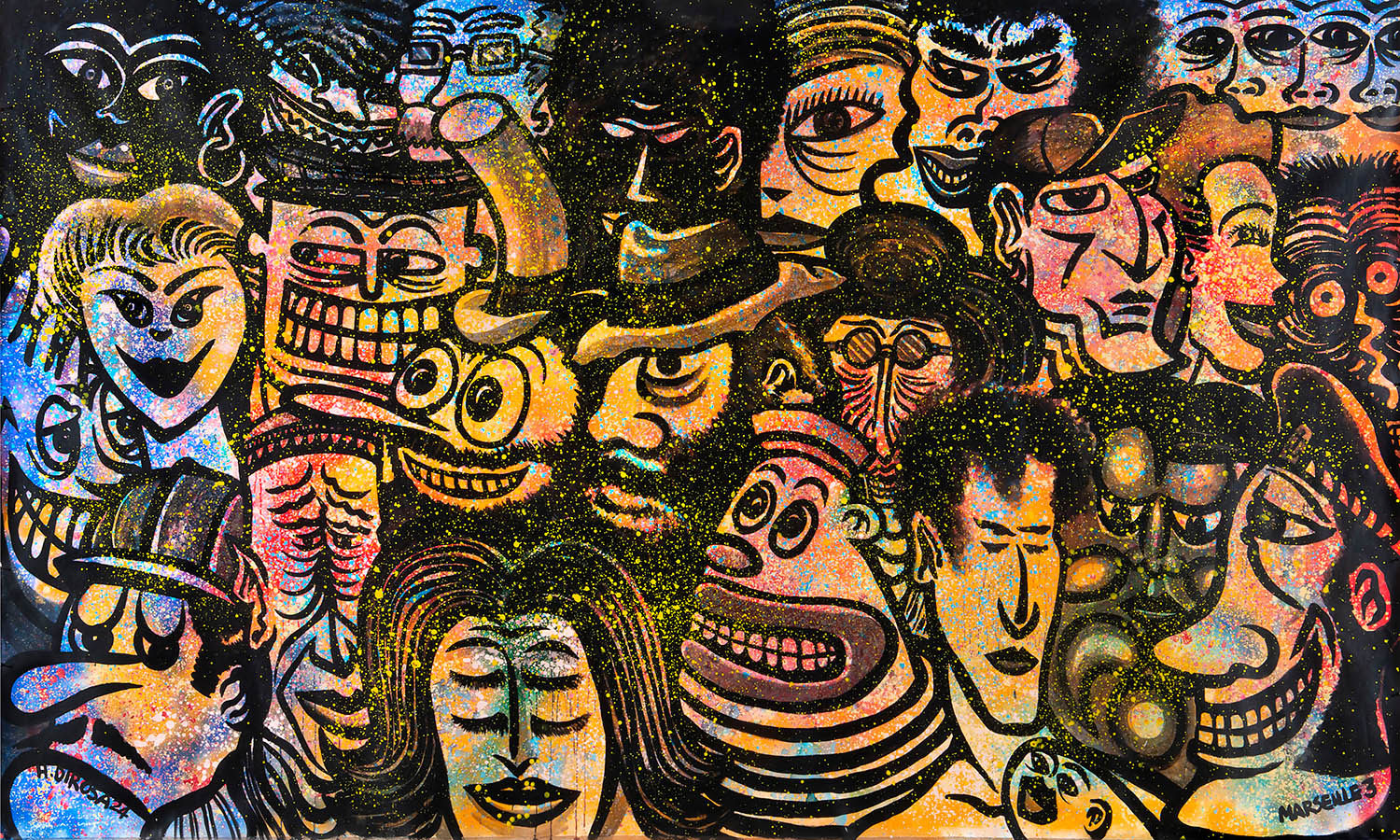

At 65, the artist exudes a vibrant energy, mixing rapid-fire explanations (coloured by his thick-as-olive-paste southern French accent) with animated gestures and a heady dose of humour. A whimsical provocateur, he challenges the norms of contemporary art with his bold psychedelic colour palettes and quirky multi-eyed family of characters inspired by pop culture, comic books, graffiti, rock and punk music, animation and global folk traditions.

The exhibition, entitled “Un Air de Famille” (A Family Resemblance, on display until 1 September 2025) offers a collective likeness of juxtaposed works through an eye-popping colour fest organised like an archipelago, featuring 15 different thematic “islands” that combine MUCEM’s forgotten treasures with Di Rosa’s paintings and sculptures. “It’s up to visitors to find the correlation,” Di Rosa adds. “Some resemble each other; for others, there may be a distant association.”

At the entrance, museum-goers are greeted by a giant papier maché mural titled “Les Visiteurs” that mirrors the population: Marseille’s rich bouillabaisse of cultures “who aren’t necessarily familiar with contemporary art,” Di Rosa notes.

[Images: Les Visiteurs © Pierre Schwartz]

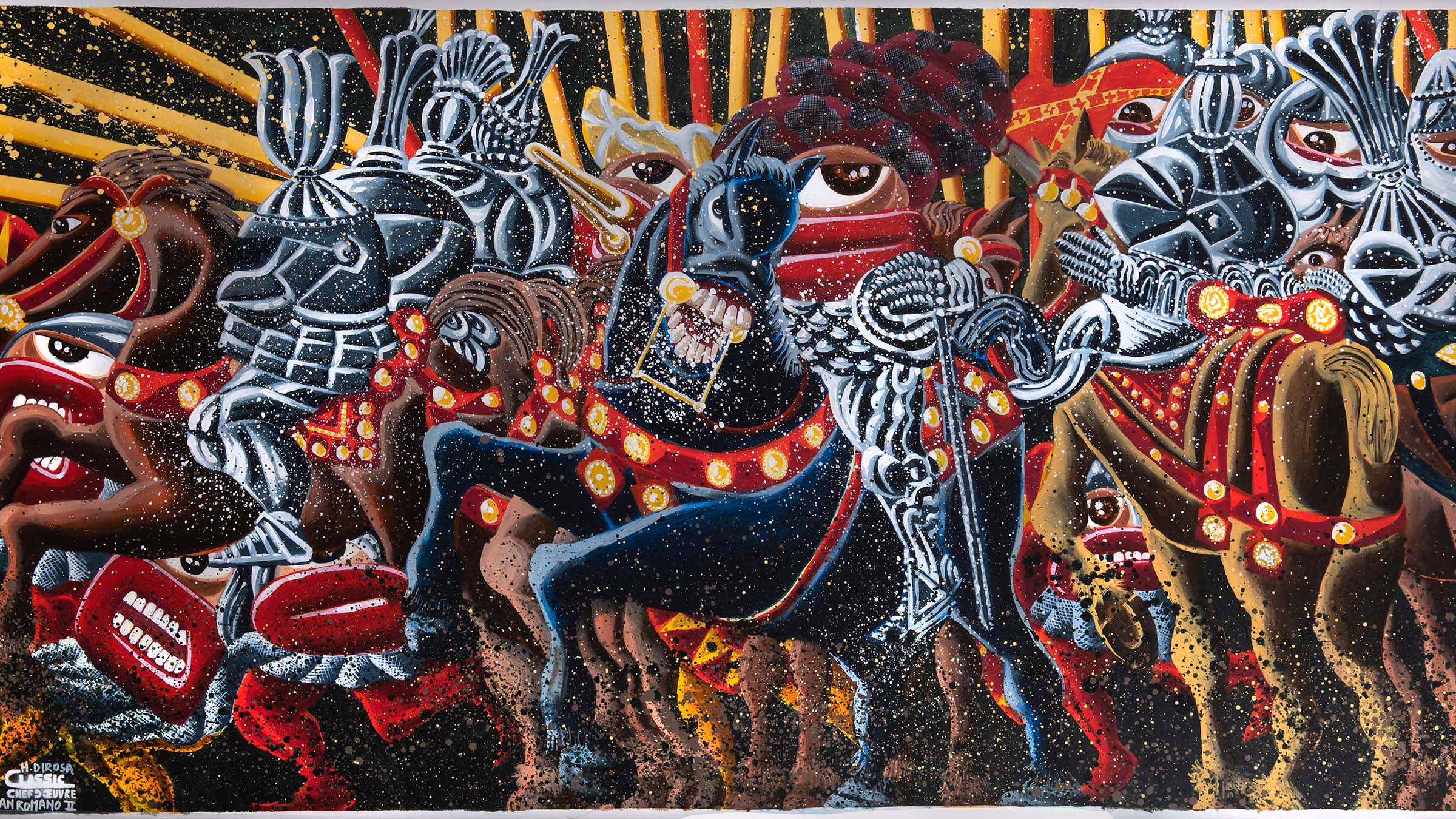

Prominent highlights include four laser-cut metallic pastel sheets with cut-out “fishnet” scenes depicting Marseille and honouring MUCEM’s architect, Rudy Ricciotti, whose modern structure features shimmering lattice panels. Another standout is a classic antique walnut armoire overflowing with a jaw-dropping array of plastic popular vintage figurines – James Brown, the Michelin Man, a Star Wars robot – from the artist’s remarkable private collection. His colourful beaded works, made in South Africa with Zulu artisans, are displayed alongside sparkly shoes once worn by turn-of-the-century French singer and dancer Mistinguett. A mechanical coal-heated copper washing machine from 1910 stands next to the artist’s African robot of wood and bronze, made in Cameroon; you’ll also see a brightly painted resin cow enshrined with ancient farm tools.

[Image: Chaussures Mistinguett © Yves Inchierman]

Among the 63 works, the artist’s latest creations include ten giant amphoras – a nod to Marseille’s ancient shipping trade – made using a pottery technique he learned at the ceramic atelier A Viuva Lamego in Sintra, Portugal. “A few years ago, I left Seville and set up a studio in Lisbon to learn about azulejos,” Di Rosa explains, referring to the traditional glazed ceramic tilework often found in churches or palaces. “And I decided to stay.”

The concept of “Modest Art” – highlighting the intrinsic beauty of everyday objects that we take for granted – has been a part of Di Rosa’s ethos since his beginnings as an artist. Born in Sète, a quiet fishing village southwest of Montpellier, he moved to Paris in 1978 to study film animation and video at the Arts Décoratifs. At this time, he also started painting. Along with his childhood friends, Robert Combas and François Boisrond, they formed what came to be called the “Figuration Libre movement” by Niçois artist Ben, marking the start of his career of solo exhibitions.

[Image: Jungle © Pierre Schwartz]

After a year in New York in 1983 – where Di Rosa crossed paths with icons like Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf, as well as presenting two solo gallery exhibitions – the artist returned to set up a studio in his father’s workshop, an old boathouse in Balaruc-le-Vieux, near Sète. By the early ‘90s, the artist had begun his ongoing “Around the World” project, with visits to 19 countries. It has been a zigzagging itinerary, he explains, of incessant travel: Bulgaria, where he learned to paint icons using an 8th-century egg tempera technique; Ghana, where he worked with industrial colours on wood panels; Vietnam, studying lacquer techniques; Mexico, focusing on clay modelling, and Africa, weaving telephone wires into wickerwork. His four years in Miami reflect inspiration from the atmosphere of Little Haiti, as well as Disney cartoons.

[Images: Charlemagne Marionnette © Marianne Kuhn / Robot Butler © Pierre Schwartz]

In 2000, Di Rosa co-founded the Musée International des Arts Modestes (MIAM) in Sète, which continues to thrive with exhibits from street art to pop culture installations with commonplace objects.

After Lisbon, and his loft studio in Paris near Barbès, what’s next on the horizon? “China, South America, maybe Brazil,” Di Rosa says without missing a beat. “But I can paint anywhere – in a small hotel room, in a Bedouin tent or in a 5,000-square-meter industrial space. Wherever I am at the moment is always the place I find most interesting.”

[Image at top: San Romano © Pierre Schwartz]

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.