When something is declared “the new kale”, do you cringe and avoid it? Same. Seaweed seems to be the latest food bearing the label “super” these days, but even if you’re a serial shunner of wellness food fads, you should give it a try. Just hear us out.

A Thousand-Year-Old Food Trend

The trendy image of marine algae would be laughable to the average Korean, Chinese or Japanese person, since East Asians have been consuming seaweed in abundance for millennia. Most modern Westerners probably know it as the wrapper that keeps sushi rice together (that’s nori), or the stuff floating in miso soup (that’s wakame), but in many Asian cuisines, it also appears in everything from crisps to desserts.

However, edible seaweed is not exclusive to Asia; other coastal cultures have been using the ocean’s produce for a while as well. Welsh laverbread is a traditional delicacy with pureed laver fried in oatmeal. The Irish have a taste for carrageen pudding (with Irish moss acting as a thickening agent), and Hawaïians love their limu, for instance in a condiment together with kukui nut and sea salt for an original poke.

So, what is edible seaweed?

Seaweed is the colloquial term for macroalgae: in other words, flexible plant-like organisms that live in saltwater (or sometimes brackish water), mostly attached to rocks. They are often resilient, capable of surviving on the most rugged and turbulent coastlines – in part because, aside from sunlight, algae can extract everything they need to live directly from the water.

There are thousands of different species, but edible algae can be roughly divided into three types:

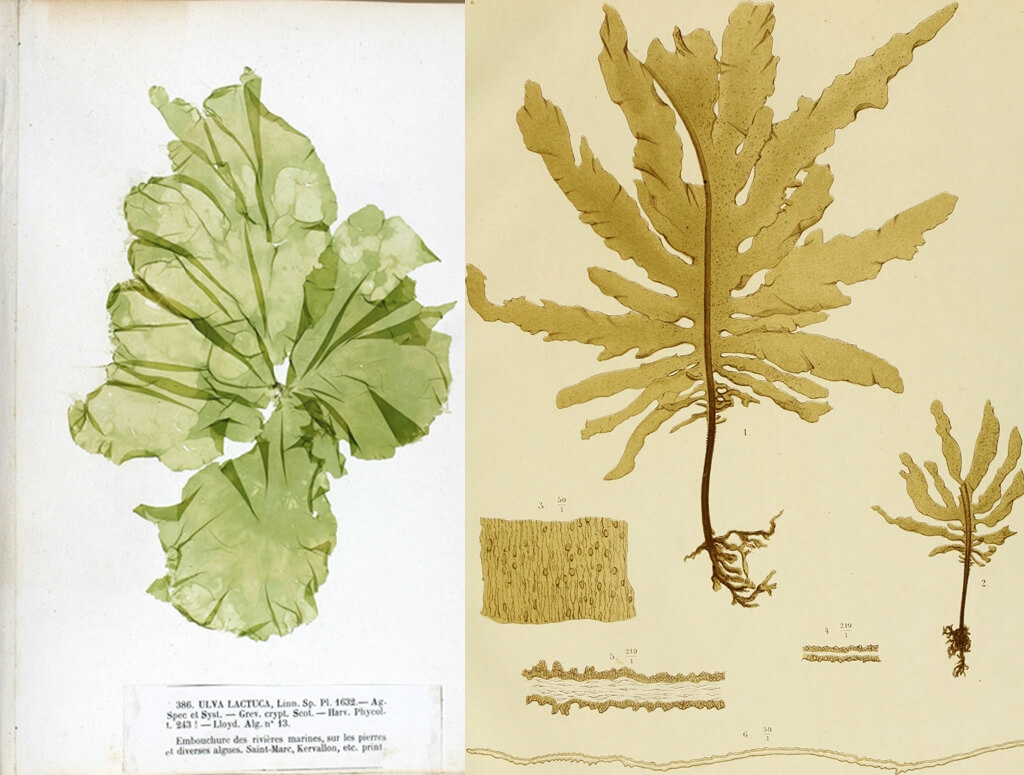

Green algae get their green colouring from chlorophyll. As such they only appear on or near the surface of water, where they can access sunlight. Ulva, or “sea lettuce”, is a common type, as is spongeweed, which is native to the northeastern Atlantic in places like Galicia, where it’s known as “alga percebe”.

Brown algae dwell in deeper waters and are often branched, with leaf- and stem-like structures. One common type that can grow quite large is kelp, of which wakame and kombu are forms ubiquitously used in Asian cuisines. Wakame, referred to in English as “sea mustard”, has a sweet flavour and velvety texture, and is often served in soups and salads. Kombu is one of the ingredients in Japanese dashi soup stock. Other edible types of brown algae include arame, alaria and sea spaghetti.

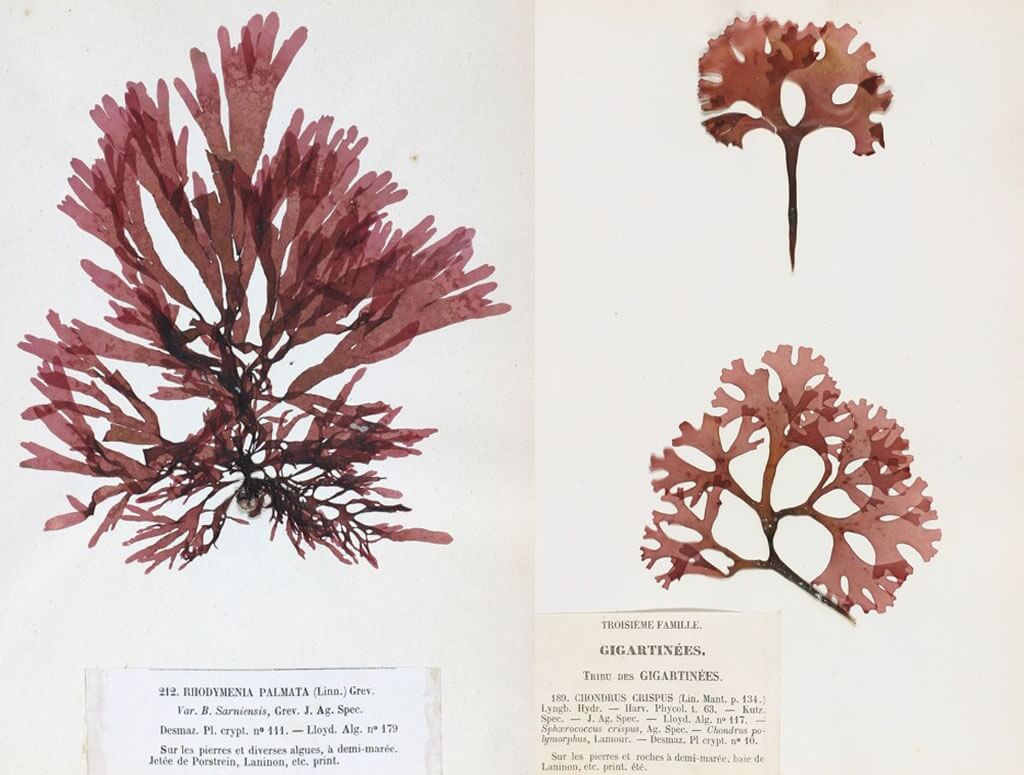

Red algae are mostly branched, but sometimes also leafy or crusty. They live deeper down than brown algae, where there’s not much light. Commonly consumed types include dulse, whose flavour is sometimes compared to bacon, as well as Irish moss, nori and laver.

Is edible seaweed good for me?

According to many different studies, this “superfood” is in fact super: seaweed boasts an impressive nutritional profile, with most types packing high levels of vitamins such as A and C, as well as B vitamins and micronutrients like magnesium, calcium, zinc, iron, potassium and, rather abundantly, iodine – which is important for a healthy thyroid. They’re also chock-full of soluble and insoluble fibres, and red seaweeds (like dulse) are high in protein, too.

Since seaweed has a naturally salty flavour, researchers are investigating whether it could be used as a salt substitute, especially in industrial products that normally contain too much salt. Some research claims seaweed can aid in weight loss, as it contains a compound that might stop the body from absorbing fat. Furthermore, researchers are exploring the possibility that daily consumption of seaweed may be partly responsible for lower rates of breast cancer in Japan.

So, is it all good news then?

Well, you know, too much of a good thing… Yes, it’s possible to go overboard on marine algae. While iodine aids in thyroid function, too much of it can cause thyroid problems. For that reason, in countries like Japan, seaweed is never eaten by itself – always in combination with other vegetables. Because of its high fibre content, it might also be a good idea to take it easy if you have a sensitive digestive system.

Seaweed absorbs essential minerals from its living environment, but at the same time there’s concern that seaweed may also soak up pollutants and heavy metals from the water. That’s why some say wild foraged seaweed from protected coastal areas might be healthier than farmed types. On the other hand, certain studies indicate that toxicity isn’t really happening. Only hijiki, found off the coast of Japan and Korea, should be avoided, since this type of seaweed does seem to soak up heavy metals, especially arsenic.

What about sustainability?

Seaweed aquaculture has been practiced in Asia for centuries, but many hand-harvesters say it’s not the best practice for a variety of reasons.

One such company promoting foraging in the wild is Maine Seaweed, run by Nina Crocker and “Seaweed Man” Larch Hanson. Hanson has been at it for over four decades, working almost around the clock during the high season to harvest algae at sea, then dry the seaweed on clothes lines on shore, before packaging and selling it.

Hanson, for one, is opposed to calling seaweed “sea vegetables”. “Sea vegetables are domesticated seaweeds grown in aquaculture, and the aquaculturist typically sets up his/her gear in quiet waters (so as to avoid losing gear in storms),” he says.

“The plants are crowded on the lines, lack substance and develop pests early in the season. Then the aquaculturist is forced to harvest early (before the pests develop) and either sell it as ‘fresh’ product (because, lacking minerals, they don’t dry out to a substantial weight), or resort to hammer milling and grinding to powders (I call this ‘making the hot dogs of the sea’) – or worse yet, shred the plants beyond all recognition, cook them, discard the cooking water (thus discarding the minerals in the solution), then freeze them in ‘convenient’ pouches, and brag that ‘these kelp noodles hardly taste like the sea at all’.”

Instead, small-scale companies like Maine Seaweed – but also Mara Seaweed, Danish Seaweed and the Cornish Seaweed Company, among others – work sustainably at sea. They harvest only during the growing season, make sure the algae can grow back quickly, and leave ample time for recovery. Most of the time they work and sell locally.

However, it cannot be denied that, in order to meet the huge demand for seaweed (particularly in Asia), there is a need for aquaculture. The total market value in Asia is about 8 billion USD per year; globally, it is predicted that the commercial seaweed market is likely to surpass 87 billion USD by 2024. Proponents claim that the growing seaweed aquaculture industry is actually good for the ocean, as it can improve water quality – specifically ocean acidification – caused by rising carbon dioxide levels, as seaweed suck up five more times the carbon dioxide than other plants. The World Bank maintains that seaweed can transform the global food security equation, in addition to the way we view and use the oceans.

Can I find edible seaweed in the supermarket?

In Japan, with some 100,000 tons of edible seaweed preparations consumed annually, the supermarket aisles are lined with products containing seaweed. But since acquiring its global “super status”, companies have begun sneaking edible seaweed into many products in other countries as well.

Actually, most of us are already consuming some form of seaweed: alginates, agar and carrageenan are gelatinous products derived from seaweed and are commonly used for gelling, stabilising, emulsifying or moulding foods. You can find them in tinned meats, ice creams, salad dressings and sauces, confectionary, desserts and more.

As for “real” foods, you can sprinkle seaweed seasoning on your (very trendy) avocado toast or scrambled eggs, or add some flakes to pasta, stews and soups. Seaweed condiments can liven up your meals as well, such as smoked Scottish seaweed-infused oil, cider vinegar or a vegan “fish” sauce.

Seaweed snacks, biscuits and crisps can curb your salty cravings, and vegan sausages with dulse or vegan chorizo with wakame can satisfy your meaty ones, with less guilt attached.

Seaweeds are finding their way into beverages as well. Kelp Stout is a dark, full-bodied beer with notes of salted chocolate and coffee, made by Tofino Brewing Company in British Columbia. Danish Seaweed developed a pale ale with brewery Herslev Bryghus, while “Kelpie” is a seaweed ale of Scottish brewery Williams Bros. Brewing Co. Welsh Dà Mhìle Seaweed Gin is a gin infused with local seaweed.

Lastly, and on a futuristic note, a company in Indonesia is creating seaweed-based packaging as an alternative for plastic.

What can I make with it at home?

Seaweed doesn’t just make nutritionists happy, it also makes many a chef’s heart beat faster. It lends that nice briny and umami flavour to a dish, and it can be served to just about anyone – no matter if they’re dairy-free, gluten-free or vegan.

Buy your seaweed fresh or dried at health food stores. Fresh is probably difficult, as most seaweeds are dried immediately after harvesting to preserve nutrients, but dried seaweeds are usually ready to be used after a simple re-hydrating soak and drain.

Of course, seaweeds are tasty when added to soups, prepared as salads or used as a vegetable in just about any dish. You’re not limited to miso soup; try a green soup with nori granola, or a lamb, mushroom and seaweed ramen. How about a salad with wakame, kale, scallions, cucumbers and creamy dressing, or perhaps a carrot and sea spaghetti salad, or even a salad of quinoa and dulse?

Chef Jamie Oliver serves grilled salmon with a seaweed salad, using togarashi (a Japanese spice mix that includes seaweed) as a “magic ingredient”. Chef Skye Gyngell adds a ginger, tamari and wakame butter to delicate grilled langoustines. And Tom Sellers’ squid dish gets an umami-rich seaweed-mushroom broth.

Seaweed adds a wonderful depth of flavour in creamy risotto. Here’s a recipe using nori, as well as another version with pumpkin and dulse. It also works well with meats: try this crispy nori with venison, or chef Josh DeChellis’s nori-crusted sirloin with shiitake and wasabi.

And to finish off with something sweet: whip up David Lebovitz’s cookies with seaweed salt, or these nori muffins. You can even experiment with brownies or chocolate truffles using dulse.

With a little imagination, you can be cooking with this delicious, nutritious (don’t call it a) superfood in no time.