Derived from the Latin ‘aperire’, which means ‘to open’, the Italian ‘aperitivo’ now refers both to the pre-dinner drink and the ritual of going for that drink.

The beverages typically consumed can be anything, really, but they’re usually dry, low-alcohol drinks, such as vermouth, or a bitter liqueur, such as Campari or Aperol. To shed some light on these tipples, we talked to Katie Parla, a food and beverage educator and journalist living in Rome since 2003. Parla, along with Kristina Gill, co-wrote the book Tasting Rome about food and drink culture in the Italian capital.

How would you describe Italian aperitivo culture?

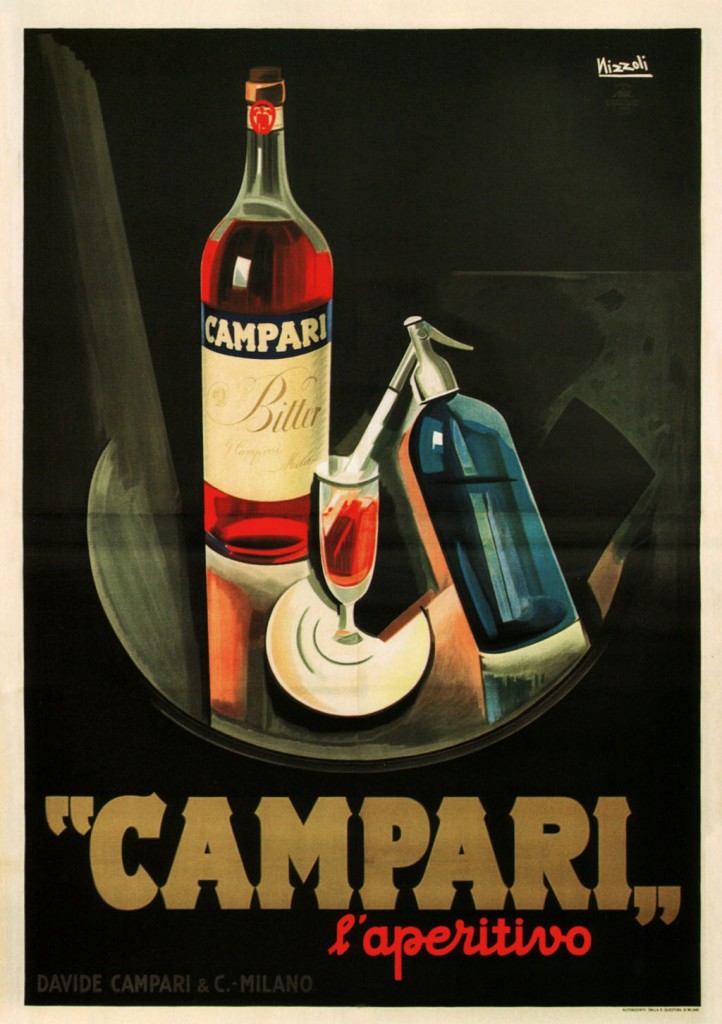

“Italian aperitivo culture used to be a very regional tradition, and the ritual of going out for an aperitif is a social tradition with roots in the north, especially in and around Milan, Turin, Padua and Venice. Many of the liquors we associate with aperitivo culture – Campari and Aperol, for example – were indeed born in the north around the turn of the 20th century (Campari’s invention was quite a bit earlier). It’s also around this time that vermouths, aromatised wines, were becoming popular. Over the past century, aperitivo culture has remained strong in northern Italy, while cocktail culture in general elsewhere lived mostly in posh hotel bars. Meanwhile, over the past couple of decades, the strong regional character of aperitivo culture has become diluted as liquor companies market new products and drinking customs change with the times.

A great example of this is the Aperol Spritz phenomenon: After the Campari company purchased their competitor Aperol, they began marketing it as the base liqueur for a wine and bitter liqueur cocktail called the Spritz. Now the beverage is found all over Italy. and not just in the northern regions of its origin. In fact, it can be found worldwide and has become a global phenomenon largely thanks to aggressive marketing efforts.

While there are some great practitioners of aperitivo culture, the word ‘aperitivo’ has sadly become associated with a sort of happy hour in Italy, and a flat fee for a drink includes snacks – neither the drink nor the snacks are intended to be quality, but rather to fill seats and maximise profit.”

It seems Italians don’t shy away from bitter flavours, an acquired taste for some. Why should one give bitter liqueurs a chance?

“I think because there are two major liquor genres – i bitter and gli amari – that are characterised by bitter flavours, we immediately associate pejorative bitterness with them. The truth is, bitterness is just one feature of these liqueurs which, when done well, are nuanced and balanced and feature bitter, herbal, citrus and balsamic notes in harmony. When mixed with spirits, they can mellow considerably and add flavour, aroma and structure to a drink.

Campari has become known internationally because of its role in Spritzes and Negronis. In what other combinations can it work well?

I think Aperol is better known as a spritz ingredient, while Campari is immediately associated with the Negroni. There are other historic drinks, however, which feature Campari, like the Milano-Torino made with Milan’s Campari liqueur mixed with Turin’s Punt e Mes vermouth. It’s also known as an Americano. The Negroni Sbagliato, which was invented in Milan’s Bar Basso, is a lighter alcohol version of the Negroni in which sparkling wine takes the place of gin. The Garibaldi features Campari mixed with orange juice. Though we don’t find much of it in Italy, you can certainly drink Campari with soda!”

Bitterness is just one feature of these liqueurs which, when done well, are nuanced and balanced and feature bitter, herbal, citrus and balsamic notes in harmony. When mixed with spirits, they can mellow considerably and add flavour, aroma and structure to a drink.

What bitter liqueur brands do you enjoy?

“I love the Cappelletti Aperitivo Americano ‘Il Specialino’, it’s one of the few naturally coloured aperitivo liquors. I also like Contratto Bitter.”

One example of how bitters can work well in cocktails is the Cosa Nostra, which is featured in your latest book. What can you tell us about it?

“Not to be confused with the Sicilian Mafia, which is far more potent than any libation, this drink is the house cocktail at Caffè Propaganda near the Colosseum. Its creator, Patrick Pistolesi, one of the pioneers of Rome’s contemporary cocktail scene, is an Irish-Italian barman with a flair for American and Italian classics. Here, he merges these two strengths, mixing a sort of Italian Old Fashioned. Bourbon is the base, joined by the Italian bitter liqueurs Campari, Rabarbaro Zucca and Fernet Branca.”

Cosa Nostra Di Patrick Pistolesi

Makes 1 cocktail

Ingredients:

¼ ounce simple syrup

1 bar spoon Campari

1 bar spoon Rabarbaro Zucca

2 dashes of Fernet Branca

1½ ounces bourbon

Lemon twist

Method:

In a mixing glass filled with ice, combine the simple syrup, Campari, Rabarbaro Zucca, Fernet Branca and bourbon. Stir until chilled, about 30 seconds.

Pour into an Old Fashioned glass filled with one large ice cube. Twist a strip of lemon peel over the glass and drop it in to garnish.

Recipe reprinted from Tasting Rome: Fresh Flavors & Forgotten Recipes from an Ancient City. Copyright © 2016 by Katie Parla and Kristina Gill. Photos copyright © 2016 by Kristina Gill. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.

[Photo credits: Opener Cosa Nostra: Kristina Gill; Portrait Katie Parla: Andrea Di Lorenzo; Negronis: franzconde/Flickr ; Campari-soda: Graeme Maclean/Flickr]

Article by Irene de Vette

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.