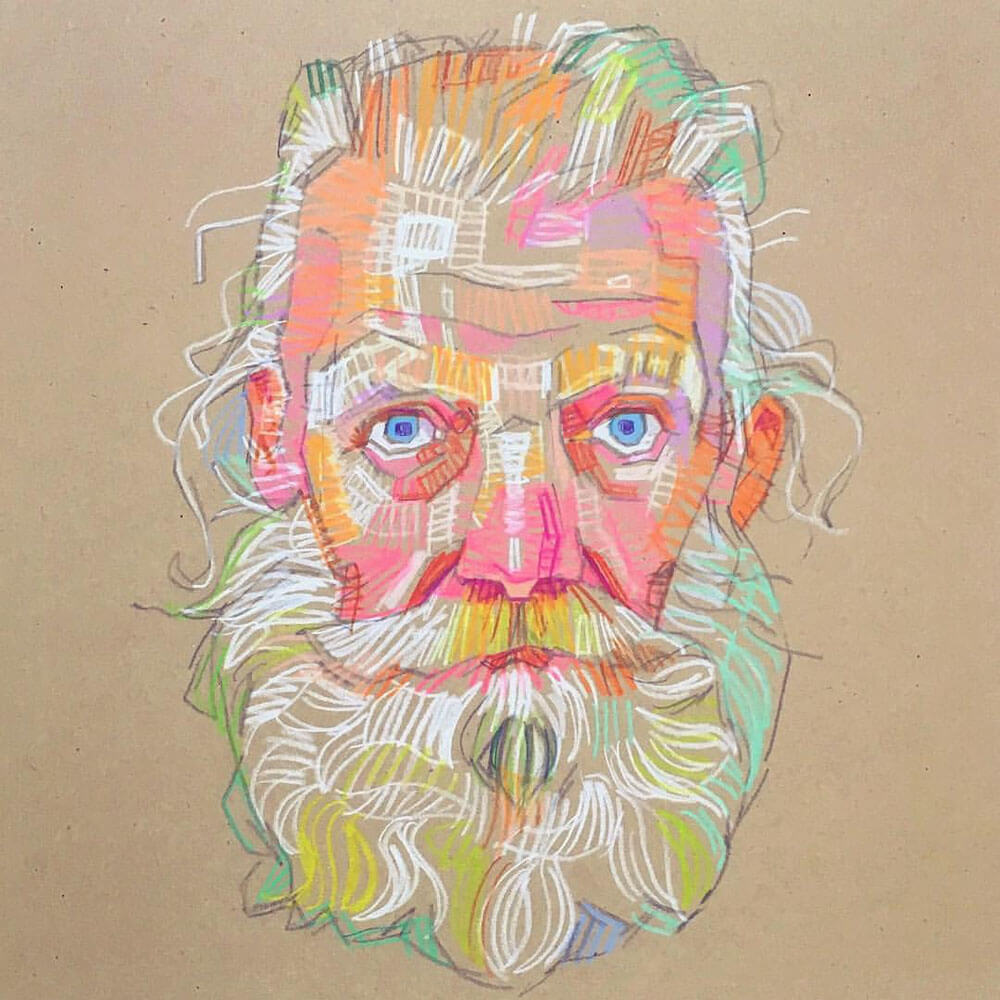

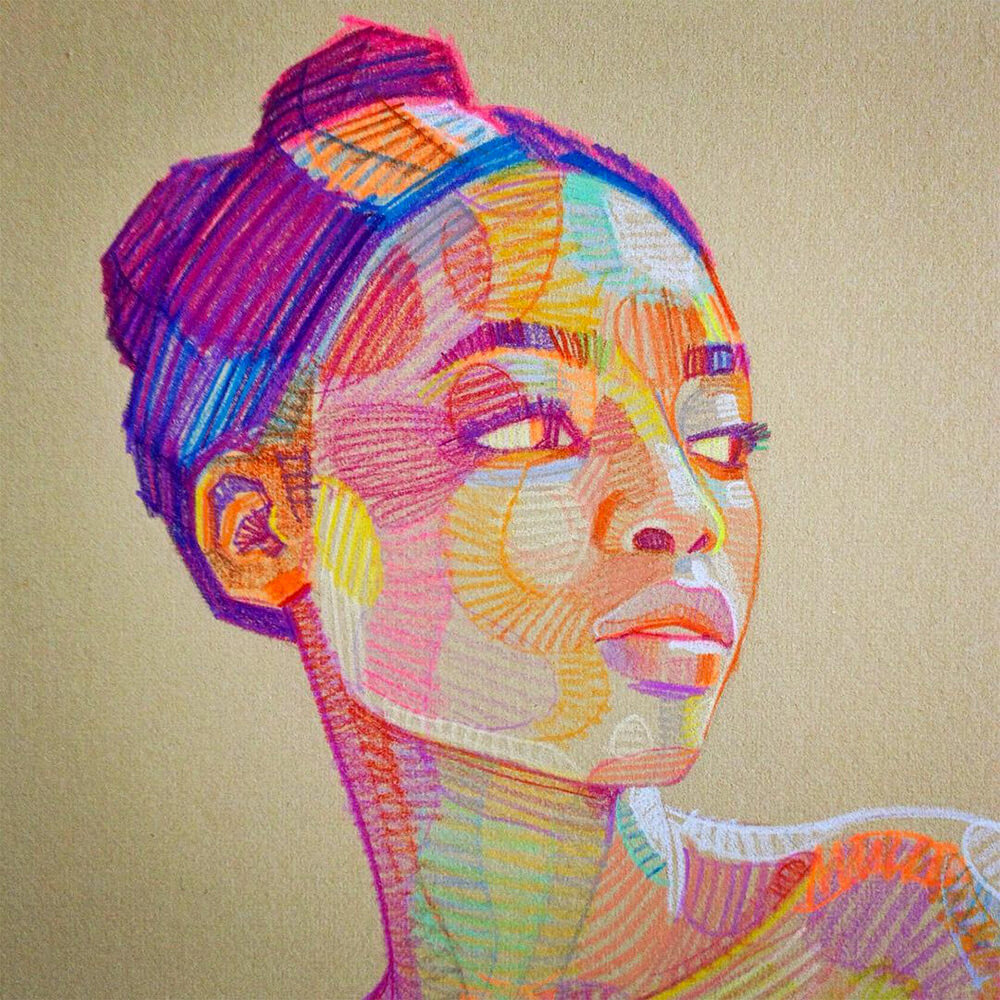

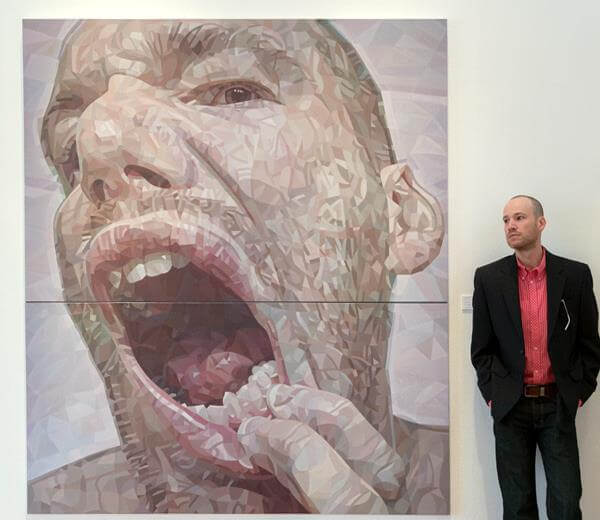

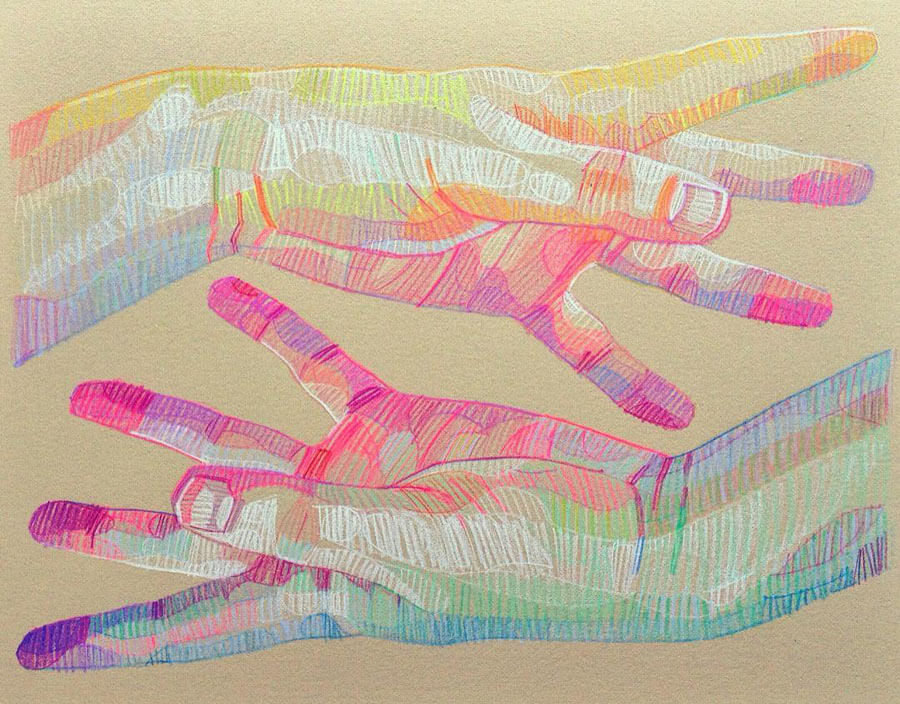

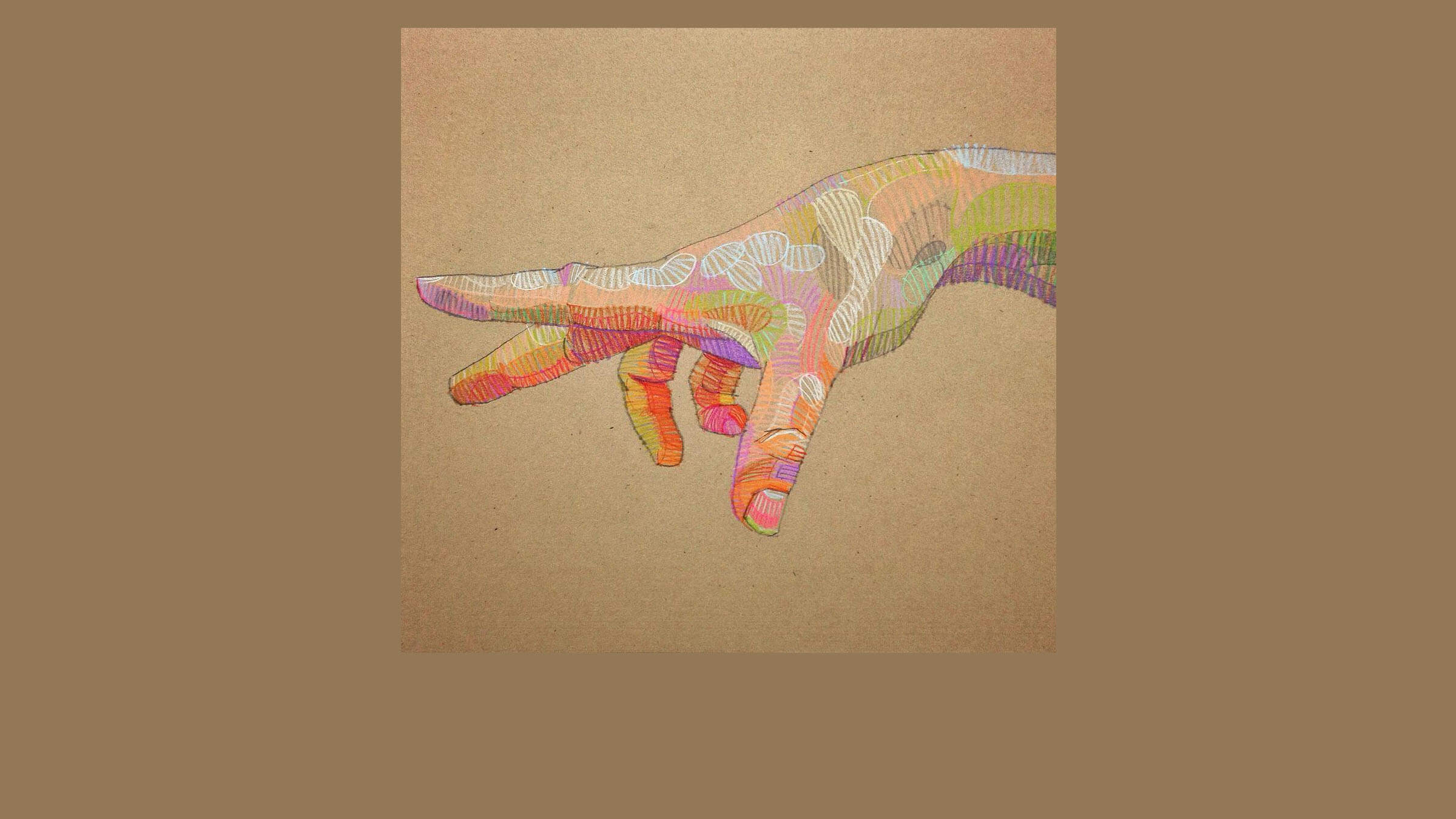

Bold colours, shading and geometric shapes combine with full effect in the work of artist Lui Ferreyra. His art invites questions about language, how we perceive nature and science. It is an aesthetic that evokes our digital age, but also extends beyond it.

Picasso is often quoted as saying: “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” Were you already fascinated by drawing and painting as a child?

LUI FERREYRA: Absolutely. My first good drawing was of the Pink Panther. My parents were so impressed and supportive of my drawings that by the time I entered the school system, I must have already had some kind of head start, because all the kids regarded me as the artist of the class. So I think I was caught up from the start in a positive feedback loop, in which the more I made art, the more I was told I was a great artist, and the more I loved doing it. There was never a time in my life in which I didn’t have the expectation of becoming a professional artist.

You moved to America from Mexico at the age of 11, which must have been exciting but also extremely challenging. Did that natural artistic curiosity and creativity as a child help you cope with any culture shock at the time?

It certainly was an icebreaker. Not only did I have the challenge of learning English at age 11, but I have also always been rather introverted. Impressing my schoolmates with a drawing of Michael Jordan or some photorealistic drawing of a rose was my way of gaining acceptance even while I struggled to learn a second language. Looking back on it it sounds so silly, but it worked.

I think of my work as a revivification of the impressionist movement, but with a 21st-century technological slant. – Lui Ferreyra

When did you realise that art would be more than just a youthful hobby, and instead something to dedicate your life to?

Again, it was such a dominant aspect of my identity that it was never even called into question. The question was always more about what art school I would choose to go to. My teachers were very complicit in all this because I seemed to always be an exception, while the rest of the class was learning some basic concept of colour theory, or rules of perspective, I would be doing a large-scale oil painting, or a mural, or some independent study of my own choosing.

How do you like to work?

I tend to bite off more than I can chew. So my typical position is to be up against several deadline-driven projects. I think I benefit from the pressure. But there’s no clear pattern. It’s not like I’m at the easel at some specific time or anything like that. Sometimes I work 2 hours, sometimes 12…

What is it like to be an artist in the digital age? How much are you influenced by ideas and inspirations you discover online?

I feel like my work explicitly evokes digitalism. In that regard I think I’m deeply influenced by the digital age. That hard-edged breakdown of visual information is very akin to video game graphics, vector renderings, medical CAT scans, satellite imaging, etc. In a way, I think of my work as a revivification of the impressionist movement, but with a 21st-century technological slant.

What artist’s work most recently genuinely surprised and inspired you?

I was late to discover Euan Uglow. He immediately became a top 5 artist for me. There’s kinship there for sure. So inspiring!

Alongside its rich colours and use of light and shade, your work heavily features geometric shapes and forms. This could be seen as a mathematical element in your work. Are you conscious of that, or do you see these geometric elements more as echoes of patterns occurring in nature?

Most of the shapes I use are intuitively discerned and defined without any anchoring to mathematical rigour. However, I’ve recently started to implement mathematically perfect design elements that interact with my intuitive shapes in a kind of matrix overlay. I sometimes envision that science works this way. Think of the planet, for instance: a sphere with superimposed meridians and longitudinal lines that run over natural bodies of water, tectonic plates, etc. They give us a way to break down the raw datum of experience and assign numbers to aspects of nature. It gives us the levers by which to understand nature – or at least exploit it.

But it’s interesting that we’re equipped with both faculties, the intuitive breakdown and the logical/mathematical breakdown. Do these geometric elements exist in nature ipso facto with or without us, or are they built into the provincial mind of our species as a kind of interface? I think math/geometry is embedded into our language systems so intimately that it’s hard to say if it’s mind or nature. It’s impossible to invoke the question without getting into philosophical arguments about what nature is apart from what we are. At the end of any argument or conclusion, there’s always the possibility that it’s an artefact of language itself – or a non-existing division that arises out of dualistic thinking.

What do you prefer about painting as opposed to drawing (and vice versa)?

I use painting to tackle big ideas. It feels important, rigorous and difficult. Drawing is fun – I often lose track of time doing it.

How do you envisage your work developing in the future?

It might sound mystical to say it, but my preferred way into art making is through the inspiration that flows out of flirting with the muse. A more pragmatic way to say it might be to say that art comes out of the cultural complex. The artist is an observer standing at the margins of society, with some kind of psychological distance; a unique perspective… Art is the low-hanging fruit an artist plucks out of the tree of culture. Art can be seen as an epitomisation of something true about us. Usually it’s a rediscovery of something previously known, but in an updated language. So my hope is that I can continue to be plugged-in in that way… to be able to reflect back, or to continue to epitomise true things about us without having to contrive some clever Master of Fine Arts-sounding thesis.

Finally, do you like your work to be interpreted with people looking for stories within the pictures, or do you see your work more as simply celebrating the essential beauty of your subjects? How should people see and understand your work?

I am agnostic about my own work. I am sceptical about my own theses and motivations. I like to use my paintings as a catalyst for philosophical speculation and to fathom intellectual depths, so I gladly invite any viewer to do the same. The only part I can authentically hold to is that I wanted to make them beautiful.

Discover more about Lui Ferreyra’s unique artistic vision and upcoming exhibitions at his website, luiferreyra.com, or follow his updates on Facebook and Instagram.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.