Each month, American Express Essentials highlights one definitive literary work, old or new, and across any and all genres. The only determinant is quality: a book that makes life more vivid, more inspiring – a gifted piece of work you want to share. An absolute must-read.

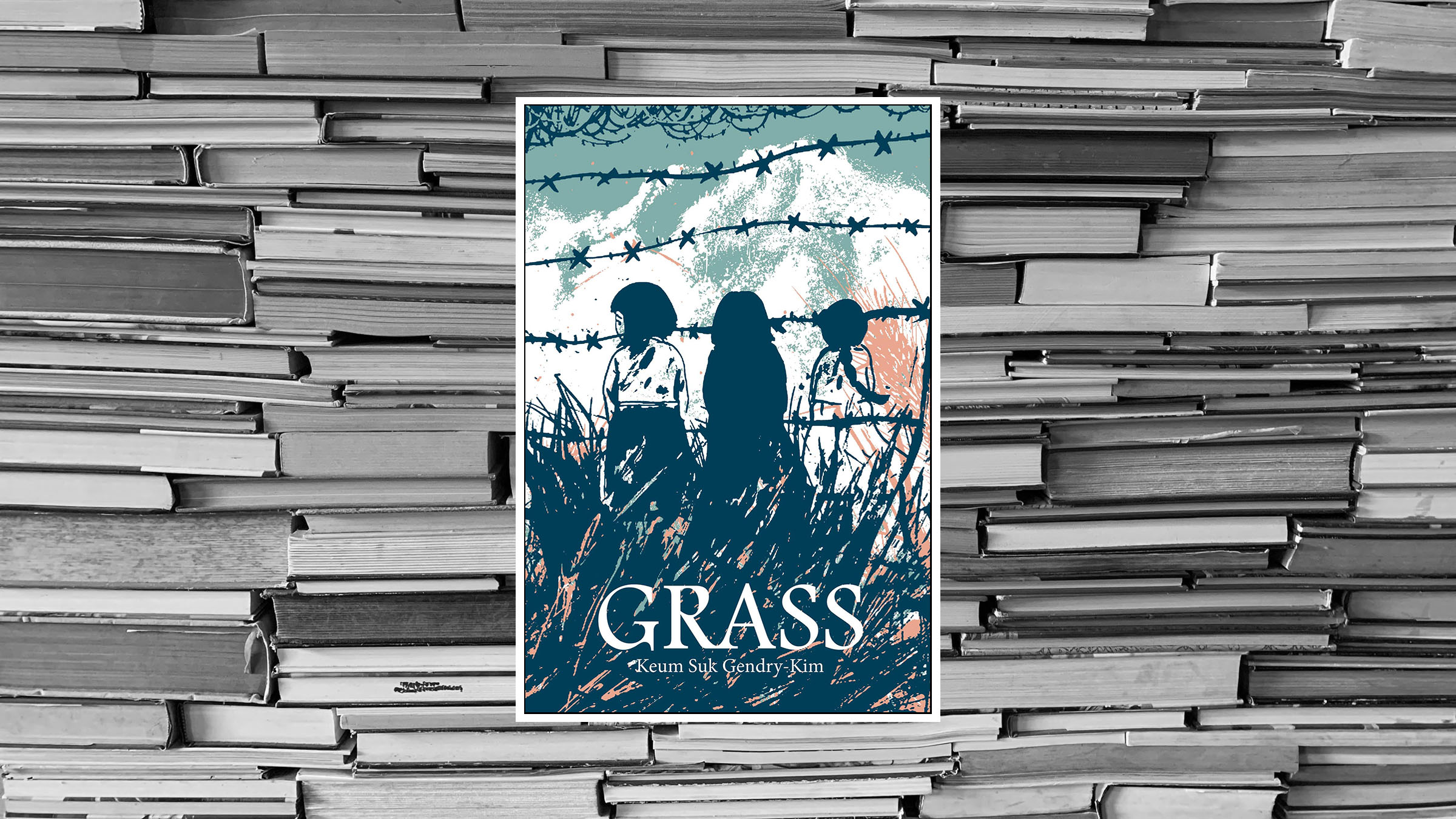

Up this month is an emotionally-challenging rollercoaster. Korean writer-artist’s Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s Grass is a mindblowing graphic novel about the horrors of war — and a woman’s fight for justice and dignity.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s Grass takes the notion of graphic novels as light, easily digestible fare, and utterly shatters it.

With each stroke of bold black ink, Gendry-Kim crafts a narrative that grips the soul. At its core lies the tragic true story of Lee Ok-Sun, a real-life Korean woman who was abducted at 15 and thrust into the horrors of life as a “comfort woman” – a sexual slave for Japanese soldiers during World War II. As such, the images in Grass are not merely illustrations, they are visceral portrayals of actual human suffering that challenge readers, page after page, to confront uncomfortable and distressing truths.

Yet, despite the darkness, a subtle undercurrent of bold resistance runs throughout the tale – a defiant anti-war sentiment that, amidst the chaos and the horror, manages to offer glimmers of hope, as well as vindication for the victims. This is not a book intended for casual consumption. It’s a profound journey that demands introspection, empathy, and a willingness to confront the shadows of history.

Lee Ok-Sun’s journey begins under a bleak sky. Born into a peasant family struggling to fend off hunger, she finds herself sold into labour as a child, forcibly torn from her loved ones at a young age. Her life’s path is littered with troubles: hunger gnaws at her belly, the chill bites into her bones, and the longing to attend school remains an unattainable dream. She simply can’t afford it.

Then, it happens. One day, she crosses paths with strange men who abduct her. Transported to China alongside several other girls, some even younger than her, Lee Ok-Sun doesn’t realise what exactly is happening. We won’t detail the events that unfold next – the atrocities visited upon our protagonist and the other captives are harrowing, hard to retell. It’s best – or rather, necessary – to read the painful account in context, but know that it may take a few sessions to confront the horrors. Despite the discomfort it may evoke, this is a narrative that demands attention – a story that must be shared far and wide.

As for the visuals, we’ve encountered few graphic novels that can rival Grass. Here, artistry transcends mere illustration, and black ink ebbs and flows, tracing with meticulous detail the contours of lush Korean landscapes and the stark interiors of Lee’s haunting memories. Each stroke of the heavy brushwork delves deeper into the emotional depths of the story, where words falter and images speak volumes. The contrast of spare narrative (sometimes only a few words per page) with intricate black-and-white artwork underscores the unutterable nature of Lee’s experiences, leaving an indelible impression on the reader.

Grass is a testament to the power of visual storytelling, captivating and unsettling in equal measure. As the story unfolds, it boldly ventures into the realm of nightmares, with threatening figures cast in shadow, their half-hidden faces reduced to sinister eyes and monstrous grins. In these chilling moments, the artwork pulsates with a visceral intensity, capturing the shattering of innocence in heartbreaking perfection. With each turn of the page, readers will be confronted with scenes that clench the heart and refuse to let go. Prepare to feel uneasy.

Amid the anguish, Gendry-Kim shines a light on Lee’s remarkable strength as she wrestles with her traumas and fights an uphill battle for empowerment and agency. After the war ended and the ‘comfort women’ were released, their pain, naturally, didn’t just vanish. Stuck in a foreign country, they struggled to return home, only to face rejection and judgement from their own communities and families once they did.

In one of the many interviews featured in Grass, Gendry-Kim asks Lee if she ever encountered “better” men in her life, to which Lee responds with a resounding “no”. From the father who sold her, to the many men who violated her, and even her husband of 50 years who mistreated and betrayed her, Lee’s journey was fraught with pain. And yet she dedicated her life to advocating for victims, to fighting tirelessly for them to be recognised and released from the shadows.

Although Lee Ok-Sun passed away in December 2022, her legacy endures through Grass and, even more powerfully, through a lifelong commitment to fighting for the dignity and justice of ‘comfort women’ survivors. Their collective tale is not one to hide – it is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, as well as a call to action for all who hear it.

Further Reading

If Grass inspired you, and you’re interested in diving further into the world of gritty, grown-up graphic novels, make sure to get your hands on David Mazzucchelli’s 2009 work Asterios Polyp or Joe Sacco’s Palestine. You might also enjoy the tenderness of Ocean Vuong’s debut epistolary novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.