As a child growing up in the ‘90s, I saw first-hand the explosive diffusion of inexpensive electronic devices – appliances, toys and gadgets. I owned a number of tiny portable radios I had gotten from children’s magazines and as gifts from family, and way too many headsets – mostly pink, but not by choice.

My late father, Libero, a professor of electronics, was both amazed and concerned by the phenomenon. Early on, he had foreseen the trend: consumer electronics were becoming disposable. Buying a new device was soon cheaper than repairing the old one. When mobile phones became small and commonplace, he knew their size was going to be an even bigger obstacle to repairs. He wasn’t wrong: nowadays, electronic waste is a huge problem (and a missed opportunity) the world must still learn to deal with.

More than 20 years later, I invite you to look at the growing popularity of kintsugi, the ancient Japanese art of repairing broken pottery, as a strong sign that times are changing. Now more than ever, we are looking to find meaning and express ourselves, rediscovering handicraft traditions to lead more sustainable lifestyles, both psychologically and environmentally. With its meditative and sustainable aspects, kintsugi fits the bill perfectly – and I simply had to try my hand at it. Little did I know that I was about to discover something even more soothing.

Kintsugi: The Art Of Showing Flaws

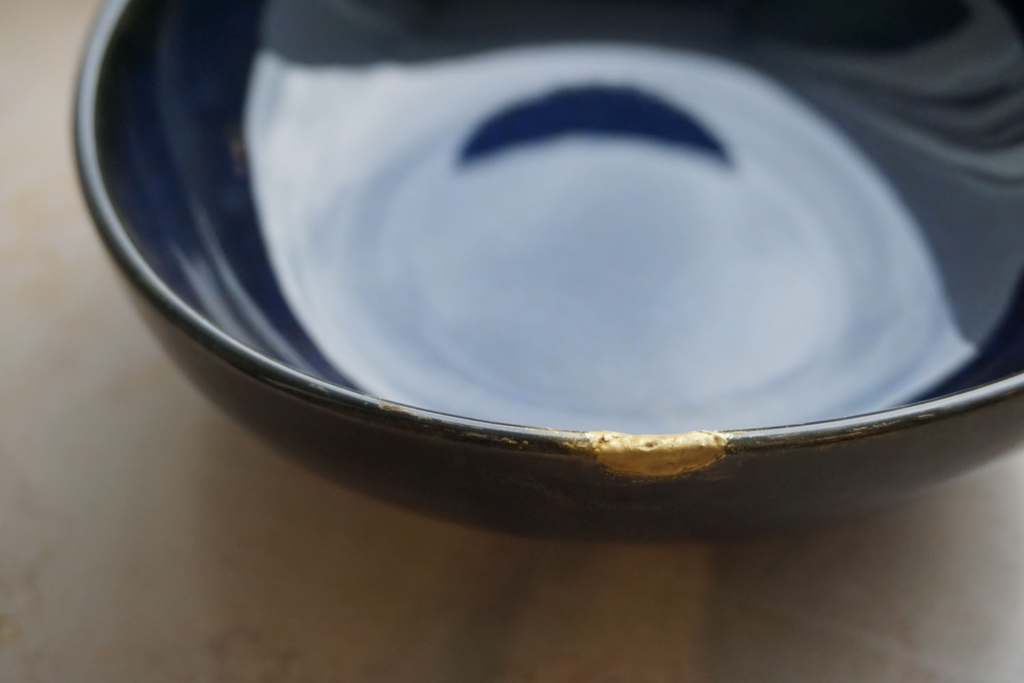

The origins of kintsugi remain mysterious; a popular theory is that it originated in the late 15th century in Japan as a way of repairing the inestimable ceramics used in the Japanese tea ceremony. Traditionally, the technique consists of coating a crack or chip with layers of natural lacquer – urushi – made from the (toxic) sap of the Asian lacquer tree. Once the lacquer has dried, a process that takes days or even months, powdered gold or silver is applied to it to highlight, rather than mask, the repaired spot.

Showing the object’s flaws as important components of its beauty is the key idea behind wabi-sabi, a central concept in traditional Japanese aesthetics. Originating in Buddhism, wabi-sabi is an invitation to appreciate beauty as something impermanent and imperfect. Far from the unattainable ideals of perfection in the West, the Japanese sense of beauty embraces small flaws and slight asymmetries, as well as exalting simple colours and some roughness as authentic, natural features.

In kintsugi, this means that cracks shouldn’t be hidden, but rather accented as an important part of the object, because they are natural: impermanence and imperfection are part of our human experience. It’s in this powerful idea that the modern affair with kintsugi originates. It’s the epitome of showing vulnerability.

Safety First: Materials & Protective Gear

First, a word of advice: practicing kintsugi means working with toxic and allergenic materials. Therefore, I strongly recommend learning it under the supervision of a trainer, and starting by repairing non-food grade vessels. Kintsugi kits are a great way for beginners to quickly obtain all the necessary gear; while there are many on the market, synthetic kits with epoxy/glue and fake gold powder are not suitable to be used for traditional kintsugi practices (nor are they food-safe).

For this attempt, I used an authentic Japanese kintsugi kit with two types of urushi (ki urushi, which is pure urushi lacquer, and Bengara urushi, a red lacquer that accents gold repairs), real gold powder, tonoko powder (a type of clay), traditional brushes, silk wadding, and several tools for mixing and polishing. I used a cardboard box as a drying chamber for the repaired pottery, but a wooden box would have probably been better at keeping the required level of humidity.

It is also important to wear the appropriate clothing: a long-sleeved shirt, gloves and an apron to protect your skin from toxic materials – especially the urushi lacquer, which, in case of contact, can cause a reaction similar to poison ivy.

In The Eye Of The Beholder

Fixing something, anything, is an act of love towards the object, something that creates a deeper bond with it (and is a satisfying activity). But doing so in a way that doesn’t hide the flaws, rather accents them, felt like something falling outside my Western understanding. I found it impossible to accept, and yet such a soothing idea. It was a clear case of cognitive dissonance.

I realise that if I want to try my hand at kintsugi, I must let go of my ideal of perfection. For days, one question occupies my mind: can something repaired be more beautiful than something new? I just couldn’t get my head around it, and yet I knew that I had to admit it was a possibility, as foreign as it felt.

[Photos: Livia Formisani]

The more I thought about it, the more I circled back to how my negative experiences changed me as a person. Every time, I had the urge to get over them, go back to my optimistic old self. Except that that person did not exist anymore – there was only a new, differently put-together version of me, something especially tough for an optimist like myself to accept. But I survived, and because I did, I changed. I became more realistic, and that, in turn, helped me become more aware of who I was, what I wanted, and how to get it.

That’s How The Light Gets In

As I go through the motions of kintsugi, I understand that I need to keep that thought in mind: perfection does not exist in nature, and hiding the cracks is not the goal – fixing them is. Easier said than done: the first time I applied my mixture of urushi and tonoko – essentially a lacquer putty – it took me 30 minutes to fill a chip of about 5 millimetres. And as I set my repaired bowl down to dry, I didn’t have many hopes it would work.

But it did. It was far from being perfect, only real. And while removing the excess putty and polishing made for a satisfactory – albeit delicate – stage of the process, I was still very much looking forward to the gold. My optimism was yet again trying to force time’s hand and rush the result.

So I took a break. I wanted to look at the repaired object without gold. Fixed and imperfect. I needed to spend some time with it, look at it ‘naked’, as it were. I understood why kintsugi is often recommended to those dealing with grief. Looking at the broken bowl, I felt the cracks in myself, but also a distant hope, as if by fixing the object I could fix myself, too. It felt therapeutic, so I didn’t rush it.

Memories of my late father, of his obstinate desire to fix everything, to help everyone, accompanied me throughout my kintsugi journey. It reminded me of his strong conviction that everything has something special in it, that everyone is beautiful, no matter how flawed they are. Even a mini disposable radio with a loose contact. Even a chipped bowl. Even broken-hearted me. As terrible as they are, our difficulties make us grow up, force us to have a look at ourselves and ultimately, push us to make the most of our time. And isn’t that the entire point of living? I had kintsugi to thank for that realisation.

Now that I knew that the gold is not the point, I felt ready to apply it. After painting the area with another layer of ki urushi and one of Bengara urushi, I finally took some gold powder with a specific brush – the Ashirai-kebou – and delicately tapped it into the air over the repaired chip. The dreamer in me loved the fairy dust; but the realist in me knew that it was what was underneath it that was important.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.